Mykola Kostyshyn

Mykola Kostyshyn was born on December 17, 1941, in the village of Fernalivka, near Lviv, into a peasant family.

At the time of the eviction in the family of Mariya and Vasyl Kostyshyn, in the autumn of 1950, in addition to Mykola, there were four children: Stefaniya, born in 1934, Roman, born in 1937, Myron, born in 1946, and Liuba, born in 1949. Mykola was the third child, later, after returning from Siberia, in 1962, another girl was born – Liusia.

In the village of Fernalivka, on the outskirts of Lviv, the family lived with their grandmother and aunt Kateryna Shchukach. His aunt was a UPA fighter, and her niece, the narrator’s sister, Stefaniya, was a liaison:

“So adults weren’t sent to say something to the insurgents, usually girls of the 11-12 years old were sent to pass the information.”

Mykola Kostyshyn remembers vividly the raid on the house of his neighbor Kolodiy. In the neighbor’s field, where corn grew, the insurgents (among them was the owner’s son) set up a hideout – “and there were always “our people” inside… There were hiding places, and our people hid in the corn.” The neighbor didn’t hand over the rations to the contingent, and when they came to ask why he didn’t hand them over, they saw there was someone else in the house beside the family. “… There was the chairman of the regional council, and also the deputy or the driver, and the third person that got wounded. He still managed to storm out, because it was a single-row village, so to speak, there was a road. He somehow managed to cross this road and fell to the ground. And it was autumn, you know, it snowed, it was cold, it was freezing cold. And he fell and hid. Then the garrison arrived, and they took the two men by the arms and legs and dragged them out of the house into their yard, but that one – he hid.” After that, Kolodiy and his wife were arrested, and Vasyl Kostyshyn took their son and hid him: “And they said who would take those children – they would shoot the whole family.” Then my father took one boy and in the evening, I remember, he laid hay and hid that boy, and the rest, the rest I don’t know who took and hid them. My mother used to bring the boy some food… So he could live there.”

When in Siberia, the father said that earlier, during the Nazi occupation, he also hid the daughter of a Jewish neighbor Bendyk: He had his own sklep [shop], even under the Polish rule, he already had his own sklep. When the Germans came they took [him] away, and his kids… He also took away her kids. I don’t know everything, I wanted to ask my dad where Pepka was, that was her name. Ah. I wanted to ask how was she… How… Because the Germans strictly ordered that if you kept a Jew, the whole family would be shot. And… Then I can’t prove exactly how long my dad kept her there, in that cellar. And, I don’t know how the neighbor… I don’t know how long my father hid her in the cellar. Because when people came to take away the Jews they just grabbed by the hand and they didn’t care if you were an adult or a kid.”

In the autumn of 1950, the family was taken to the transit prison No. 25 on Peltevna street – to the place where before 1944 there was a ghetto. The narrator said they knew they would be evicted soon – “but we knew that people were being evicted in the village. But we had no idea what Siberia was, neither my mom nor my dad knew much. We were evicted to Siberia and that’s all we knew.”

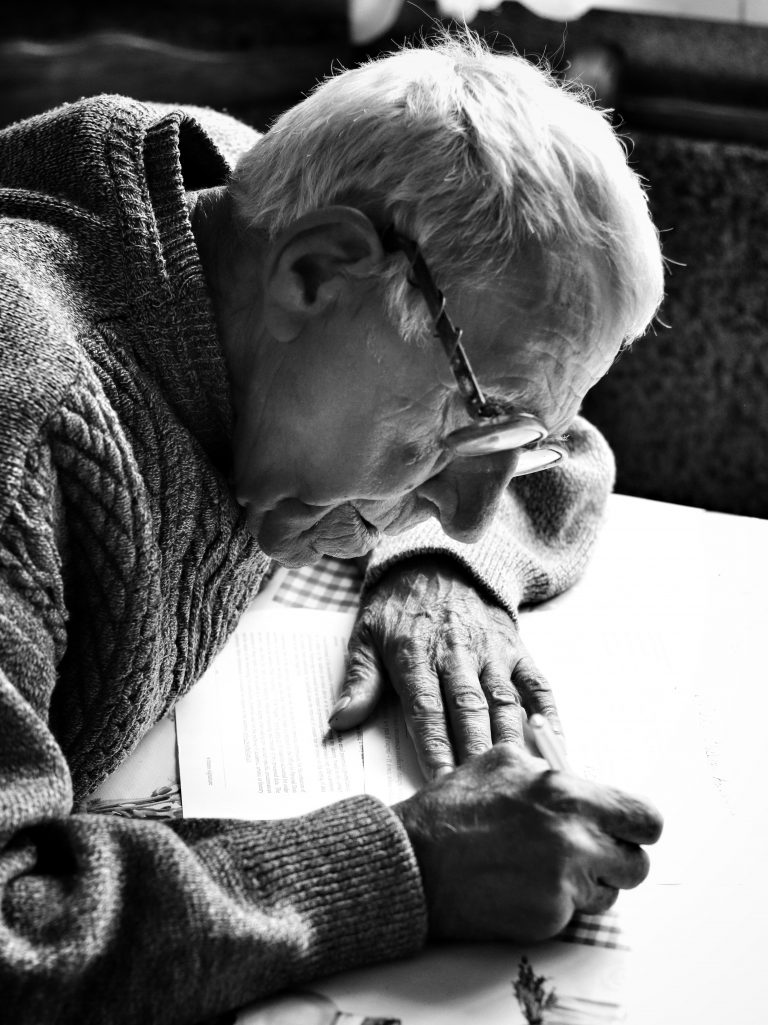

In prison, the prisoners tried to resist the guards with small deeds: Oh, and our people, no one cared to read the political information. When they [the guards] came in, our guys, I remember vividly, they took the newspaper upside down and pretended to read it. They took it upsidedown. And they [the guards] were looking at that… I still remember, usually, three or four men came in. They said [in Russian]: “Listen, how are you reading it? He takes the newspaper, turns it over, “this is how you should read it.” They also mocked those Muscovites as much as they could, our people didn’t want to be afraid, even though they were going to face death.”

On the day of the arrest, when describing the property of the evicted, the narrator’s mother said the whole farm belonged to her grandmother, so later her grandmother could send her relatives small “packages” to the prison – “there were many things: milk, meat, eggs, and also vodka, so we had, we had everything in there”.

“The train cars have arrived. And those were the simple train cars, made for transporting cattle. The train cars arrives and got attached. I remember, we were also escorted there – on the one side there were people with rifles, and also there were dogs. Every 3-4 people there was a dog, a dog, soldiers had dogs. And so they took us all, they took children, and all of us to the carriages, and put us in the carriages. And transported us to Siberia.

Most of all, Mykola remembers the moment when soldiers came inside the train cars on the stations and asked if there were dead people. There were eight families traveling in the train car together. The narrator remembers for sure that no one got sick because everyone was afraid – “as soon as you became weak, you had to die, who could survive just being sick…”

The family was relocated to the Khakassia Autonomous Republic in the Krasnoyarsk Territory – first near the settlement of Timirov, and later to Shora. In this region, the settlement depended on the reserves of deposits, so when production was completed, people were transported to other places nearby:

“We lived there, don’t think that it looked like this house, where I live, it’s good that I’ve already built this house with my wife. I can’t count how many times and to what places we were transported. We checked in every nine days so that we would not run away. There was the commandant’s office and my father and mother checked in there every Saturday. We could only leave for a maximum of ten kilometers from the place of residence. And they brought us… They brought us, they gave us an old house there, there were cockroaches inside. I remember during the night, the cockroaches were falling on people, children, on my mother, that’s how a house usually looked that they gave to families. We usually lived at one place for 5-6 months and then we were moved to the next place. I also remember we were taken to a club, I remember, there was a huge wooden house. And there was a Russian stove, I hadn’t ever seen such a stove, I still remember it. And the ceiling was two or three meters. And so we lived there too, we didn’t live long there. The car arrived at the down: “Go to the car, we are taking you to a new place.” And they transported us, they transported us, and at that place, there was no firewood, nothing, and how could we heat the house then. Then my mother had a stroke right away, she couldn’t walk, she couldn’t sit because she was often cold. Because for my dad, he gave him some work there, and my mother, my mother was as they called her… They called her… When you have many children, how is it called? Mother of a large family. My mother didn’t go to work, it was necessary for her to look after children. So my dad had boots, a quilted jacket, underpants – it was easier for him, and mom had nothing – she had no sportswear, no underwear, no sportswear, all she had was a dress she brought with her.”

In Siberia, Mykola Kostyshyn also continued his studies at school, but he also had some difficulties there:

“I can tell you how I was expelled from the seventh grade. There was a history lesson. Well… And the teacher says there is no God. And my mother taught me a lot about God. My mother used to work with my older sister, she went to church. When evening came, she made us pray. And I started speaking, everyone was silent, and I told them, and I told them – God exists and will always exist. Well, and that’s it. They called my mother to the school, but they didn’t kick me out. They called my mom in and said, “We teach children there is no God, and you teach – as if the mother teaches – that God exists.” And the mother answered, “I teach children that God exists.” “Then we do not allow your child to attend the school” and I was not allowed, but then I went to the eighth grade later. But it was no longer proper studying, I started going to work and I wasn’t attending all the classes.”

In 1958 I managed to get a job: “And there was a barrack, the office was there and our barrack was there, we lived in the barrack. And a was walking towards me – “Hello, hello, I’m hiring.” And I immediately guessed and said: “How much will you pay?” – to that boss. “One thousand two hundred rubles,” he answered. So I agreed. Dad worked in the mine and made 900 rubles, and here I was offered 1200. I came home and told my mother. Mom said: “You’re silly, your dad works hard in the mine and has 900 rubles, and you say you will be paid 1200… They are going to fool you like a small kid.” But I didn’t listen to my mother and accepted the job offer. And then I had to carry rails, they measured everything, I was carrying the rails all summer […] And at the end of the month he [the boss] came and paid, and my mother was so happy. It was one thousand two hundred rubles, it was a lot. I worked there for three or four months, and, and I gave the money to my mother.”

His parents and sisters returned in 1962, and Mykola and his brother still had to earn money so that the family could settle in Ukraine. In 1964 the brothers returned. Upon his return Mykola was drafted into the army, served in the radio troops:

“I was assigned [received a residence permit] and the next day I was taken to the army, imagine… I was taken to the unit which was related to the Warsaw Pact, you know. I was soldiering, those generals came from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, I was saying [to my friends] “To be honest, I would prefer to be in Siberia than in this army for three years.”

Mykola was demobilized in 1967, he lives in the Malekhiv village, Lviv region.