Oleksandr Lasovskyi

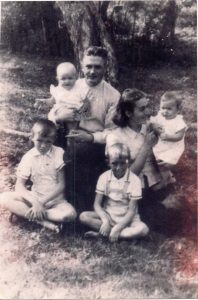

Born on 12 January 1940 in Halych town, Stanislav (since 1962 – Ivano-Frankivsk) oblast to the family of Viacheslav and Liubov Lasovskyi. The Lasovskyis had four children: Yurii (born in 1933), Bohdan (born in 1935) and twins Oleksandr and Oksana (born in 1940).

From the cleric family

Oleksandr’s grandfather and father were clergymen of Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. His grandfather from Yanovychis family was a parish priest in Halych. Initially his father did not have his own parish and was assisting another priest. Then he was moved to Tustan and later to Zhydiatychi village (presently Hamaliivka) in Lviv Oblast where he served at the parish. Following the pseudoassembly in Lviv in 1946 he did not convert to orthodoxy, but secretly performed priest’s duties: “When the prohibition was imposed in 1946, priests would conduct a service at home, and people would come to their houses”.

Deportation

Viacheslav was deported in 1950 with his family for his refusal to convert to orthodoxy and his secret performance of priest’s duties. They were brought to the transit point in Poltviana street, to the transit prison No.25.

Oleksandr was 10 years old and he remembered the conditions his family ended up in: “Two-storey barracks surrounded by a high wall; there were towers with armed sentries there, carrying rifles and all. We were sitting there; there were barracks, wooden plank beds and everyone was sleeping on those plank beds. Anything they were able to take with them was used to sleep on. A piss can was in the corner… A wooden pail to ease oneself, and, I don’t know, perhaps once a day they let us go outside to go to the toilet; whenever possible, they kept us in like that”.

One day he managed to have a peep on the adjacent territory and see prisoners: “Sometimes they let us out. I remember us going to that yard, and there was a fence behind it, a wooden fence, I think; s– o I looked through the crack”. There were prisoners, maybe political ones, and they were walking in circles, that’s what I noticed. They were our neighbours. We were taken out, deported, and I believe they were arrested”.

In over a month’s time they were taken to the railway station on trucks, together with other deportees, and put on an echelon to be transported to the special settlement.

The road to deportation

A part of echelon was detached somewhere on the way. Oleksandr does not know where it happened.

However, he remembered the conditions in which transportation took place: “There were up to fifty people in the wagon, or maybe even more. There were stoves. You know what stoves were, those metal ones. A stove on one end, near the door, and another stove on another end. It was even possible to cook something on those stoves. Well, but what could we cook? There was no toilet, a hole was made in the floor near the door, and we had a carpet, so we used it to screen that hole and turn it into a semblance of a toilet, and that’s how we travelled”.

The echelon stopped regularly: “We were travelling and often stopped. They gave us some food, some cheese to have a bite. And if people died on the way, they just threw them out of the wagon”. Once the echelon stopped because of the holidays, and people were left to their own devices: “These were October festive days, and they put the echelon on the spur end and went off to celebrate and left us there, hungry, cold, with nothing”. Oleksandr recollects that villagers had more food on them than townsfolk did: “I thought so many times: “Gosh, they’re eating chicken and I can’t”.

In Buryatia control over special settlers eased up: “I remember when we stopped somewhere, Buryats were selling fish. It was delicious – smoked burbot. We were buying it from them on the way”.

At the special settlement

The deportees were brought to Buryat-Mongol Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. People were taken from the railway station to the special settlement in trucks. First, they were put up in an old community club, and then in barracks where prisoners used to live. Six people from the Lasovskyi family could hardly squeeze into a small room.

The newcomers were made to sign documents acknowledging their awareness that they were exiled forever. Oleksandr’s parents had to visit the superintendent’s office every week to sign out.

Sashko and his sister Oksana got into the 4th year of school in the special settlement.

“We went to school, it was quite a long way to go, across the railway, and, you see, we were walking large distances”. Two older brothers went to work. Mother was responsible for taking care of the large family, and father was helping her: “It goes without saying that my mother was cooking, and father went to work every day, so she had to cook and keep the house”.

Father secretly conducted services and performed rites: “Father secretly held service there. The room was small and everyone was visiting us during holidays – Christmas or Easter, baptising or funeral. Everyone was coming to us”. Still, it was impossible to keep a secret for a long time: “I even remember the moment – my father is holding the service, and a man comes in – well, wearing a peculiar blue hat; and my sister was little back them; and she didn’t let them in”. He was offered to convert to Orthodoxy and be rewarded by a parish in Irkusk. Still, Father Viacheslav refused again. The priest’s family was punished for it.

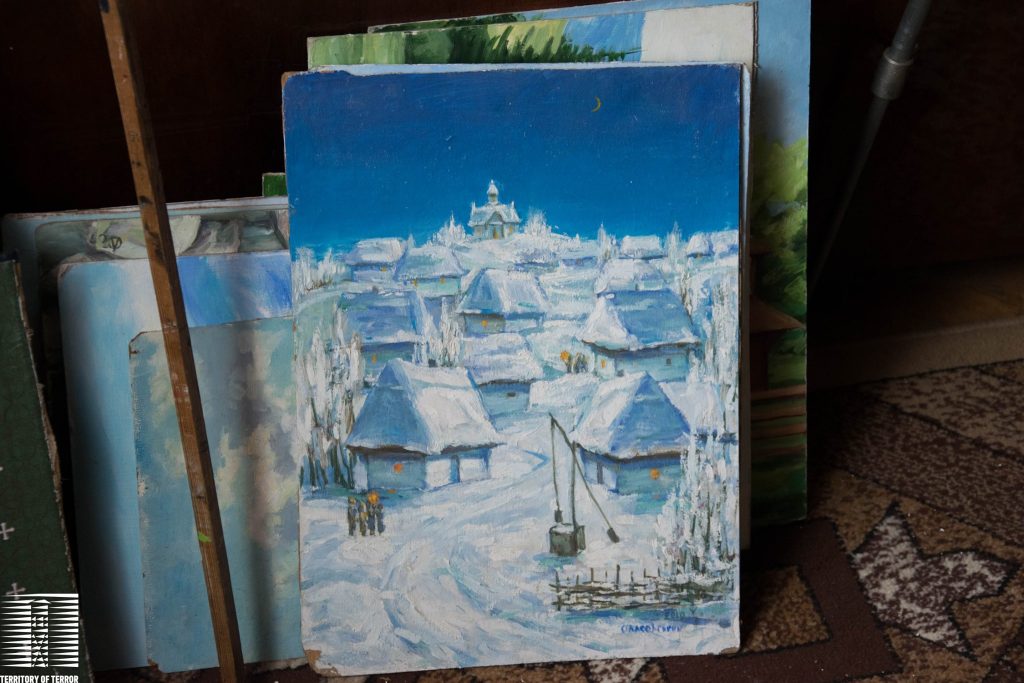

They were taken to a faraway settlement in taiga where there was no school. “Our family was sent off… You might remember the film“Girls”[“Divchata”]. It’s a beautiful Soviet movie featuring the taiga similar to one we had been taken to”. Besides Ukrainians, there were many Moldovans there. That’s why special settlers called their settlement Moldavia. All adults were felling trees. Middle brother Bohdan started working as a logging truck driver. Older brother, Yuriy, had a nice singing voice. Oleksandr does not remember the circumstances under which he managed to leave the special settlement.

His brother moved to Ulan-Ude and was singing in the local opera theatre choir there. He was a choir singer first, and later he started performing small solo parts.

There was no school, so special settlers’ children were playing outside the entire time: “I must admit the nature was beautiful. Syberia, those pine trees and pignoli. We were eating those pignoli, like you’re eating sunflower seeds here. Grass was huge, tall and beautiful. Everything was there: Bilberries, blueberries and whortleberries, all these berries. The nature was gorgeous there”. When the new school year started, Sashko and her sister returned to the previous settlement. Former neighbours took them in, and they continued their school studies. In addition to going to school, the children had to work. “We had a side job, for there was no gas. We were boiling glass and cutting wood, and put those logs together, making a stack of wood”.

In 1953 father and mother moved to Ulan-Ude where their older son Yurii lived.

Coming home

After Stalin’s death children of special settlers were taken off the register and allowed to return home. As Sashko and his sister were small and couldn’t return on their own, they travelled together with the school principal’s family.

Grandparents and aunt met them in Lviv. They had constrained living conditions, but the family stayed together. Then they got into school.

Meanwhile, their parents moved to Ulan-Ude to their older son Yurii. Father started working as a school janitor and mother took a job of a cleaner and cloakroom attendant. The school principal sent Viacheslav Lasovskyi to a handicraft teachers training programme.

The family returned to Lviv in 1958. Still, Father Viacheslav couldn’t perform priest’s duties, as the Church was banned. That’s why he got a position as a handicrafts teacher at school. Still, he resumed his priesthood later. He secretly served in the Catacomb Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, like his father used to.

His elder sons came back later. Yurii Lasovskyi first worked as a member of a choir in Lviv Opera and Ballet Theatre, and then ran an opera studio at the theatre for twenty years. Bohdan was working as a farm machinery operator in Obroshyno village.

Oleksandr graduated from school and went to music teachers college. He was drafted to the army during the third year of his studies. Following his military service, he graduated from Lviv state institute of applied and decorative arts. He was working as an artist (first a chief artist and then art director) in the Raiduga plant in Lviv which produced crystalware and stained glass. The President Leonid Kravchuk awarded Oleksandr a distinction of “Distinguished Artist of Ukraine”. He worked at the glass department at Lviv National Academy of Arts for 10 years.