Sofiya Zubrytska

Sofiya was born on June 4, 1942, in the village of Uhersko in the family of the Galician intelligentsia.

Her grandfather, Mykhailo Mykolayovych Zubrytskyi, was an accountant who worked in the Raiffeisen Bank branch in Stryi and in the village administration in Uhertsy: “He was a highly intellectual person, he knew languages, wrote texts, poems. He described and wrote down the history of Uhersko. We, as his descendants, compiled this history and transferred it to the archives of the village of Uhersko, Stryj district.” Her grandmother was the head of the women’s council – possibly a group of the Union of Ukrainian Women. Her father, Ivan Zubrytskyi, worked as the chief accountant of a group of ethanol plants. Mother Mariya came from the Tarnavski family from the village of Dobryany. Her mother’s eldest brother Mykola was in the underground movement (he blew himself up with a grenade during the raid). Her mother’s brother Dmytro was taken to forced labor in Austria, later he returned and worked at a distillery in Uhersko; the youngest brother, Stepan Krystiv (mother’s half-brother), was in the SS Halychyna division.

Working as a chief accountant, her father helped the insurgents: “Since he worked at the ethanol plant, it means they took some alcohol, and as far as his sisters’ brothers-in-law worked with him at the plant, and later he returned from Austria, her mother’s brother Dmytro returned from Austria, and they were transporting alcohol to the boys in small portions. And the boys had the opportunity to sell it, or use it, that is, he helped with what he could.”

In 1948, the Zubrytskyi family moved to Stryi – “Why? Because my parents wanted us to get a good education.” Brother Volodymyr, born in 1935, and sister Daria, born in 1938, continued their schooling, while Sofia went to the first grade.

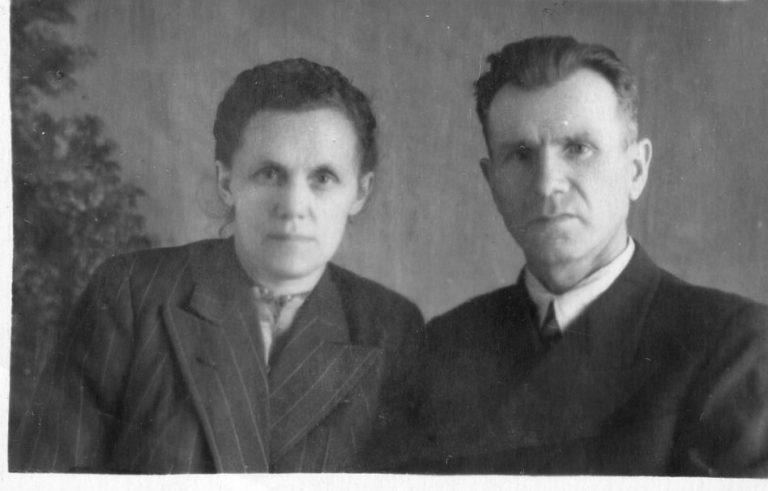

(photo: Mykhaylo, the narrator’s grandfather while working in his office)

The family was arrested on the morning of December 19, 1949 – the children did not even have time to unpack gifts for St. Nicholas Day. Later, the parents said they bought a piano for the children because children were studying music and, in particular, playing the instrument.

They were taken to a transit prison in Boryslav. On the same day, two father’s sisters, Mariya and Anna, were brought there with their families. Later also a third sister Rosalia was taken to Arkhangelsk. During the family’s stay at the transfer point, Ivan Zubrytskyi was offered cooperation, but he refused – “And they [Mariya and Anna] were taken to the Krasnoyarsk Territory, and as my father did not agree to cooperate, we were sent to Khabarovsk as a revenge.”

During her stay in Boryslav, Sofiya Zubrytska fell ill:

“There were a lot of people in that cattle train car, and I was very sick, all in pain. My dad was the car leader, and he just asked everyone not to mention there was a sick child here. If they said it, that child would be thrown out right away, because sick people were thrown out, you know. Fortunately, people still showed decency, humanity, no one said anything. Women went out somewhere at certain stations, bringing food and water, including our mother. “

Upon arrival, the doctor examined the special settlers: “It was my turn, he examined me. Well, there is a seven-year-old child with huge blue eyes. He looks at me like that and says to me, “I’m sorry, but I have little faith that you can save her here.” Thanks to the fact that the mother took the jewelry from home, she was able to save her daughter – she exchanged jewelry with the locals for “butter, honey.”

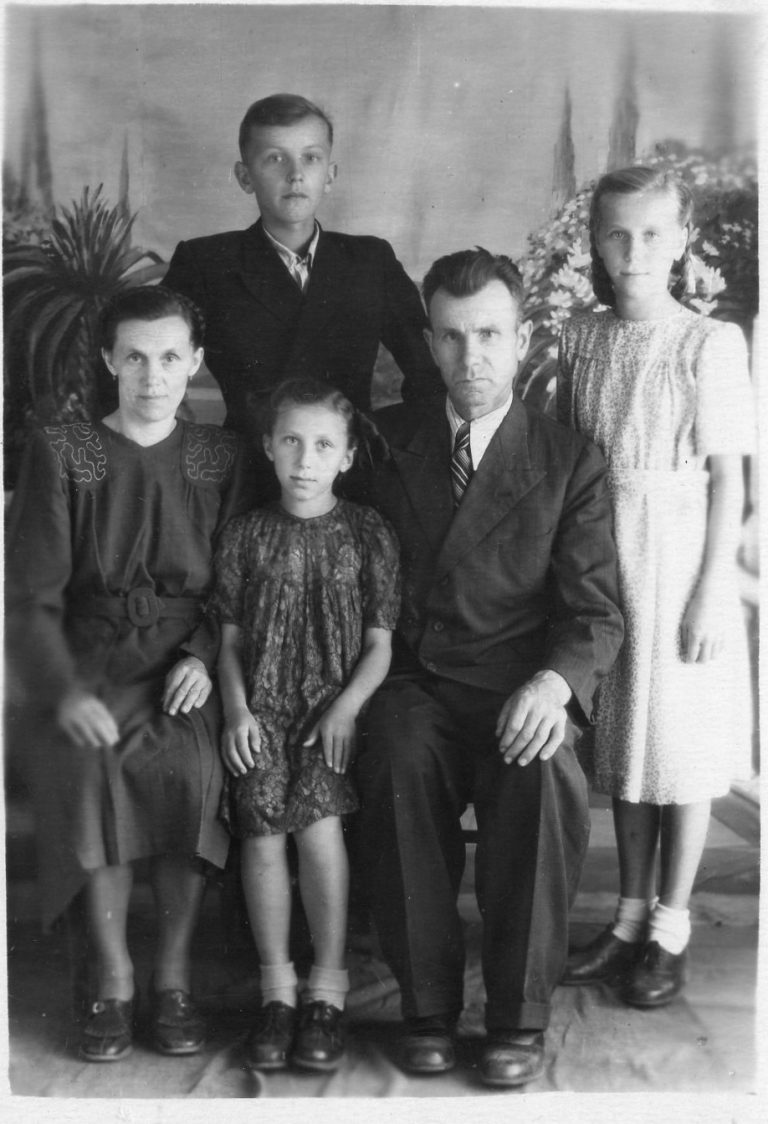

(photo: Zubrytsky family photo)

At first, the family came to the settlement without a name – “There is no name, because it was in the woods, in the taiga. Six months later they were moved to the “village of Khor, on the river Khor.” The village had timber rafts and two hydrolysis plants.

Her father was sent to work as a logger, later he got a job as an accountant. Her brother worked on a timber raft, and her sister worked in a factory:

“Everyone worked. Although we were children, I told you, and we were children from a quite wealthy family. I was the chief shepherd of the geese, my father let the geese outside, and I grazed the geese. And my brother and sister helped too, they were planting potatoes, everyone was working in the summer. My mother had heart issues, she fell ill during the war, my mother did not work, she was a housewife. “

In addition to working at a lumberyard or factory, family members tried to “earn extra money” and bring something home:

“And what I also remembered when we were little, just when we got there, to the Khor village. Somewhere the river flowed, and behind the river there was… I don’t know. There was a plantation where currants were grown. And there was a rule, if you collect ten buckets of currants, then the tenth bucket is yours. My mother took all three of us in the summer, and we went to pick those currants, and then we had some for us too. People took dad with them on a fishing trip and were fishing salmon. We had frozen salmon for the winter. I grazed geese, the geese were frozen later too. The berries were frozen, there were amazing tomatoes, like that, wonderful tomatoes.”

The children also received parcels from grandparents:

“My grandfather once sent us a parcel of apples. A parcel of apples. Of course, they all rotted. But they sent it to all grandchildren, and there were many of us: in Krasnoyarsk two families, and ourselves. Before the beginning of the school year, he sent a parcel to each of them separately. There were 10 of us, 10 grandchildren. Everyone had their parcel. There were all the supplies for school: notebooks, rulers, pencils, there was everything needed. And andruty, the waffles. It’s always been for us… everyone knew their name. For every birthday, he sent us letters in poetic form, it was a nice thing to remember them by.”

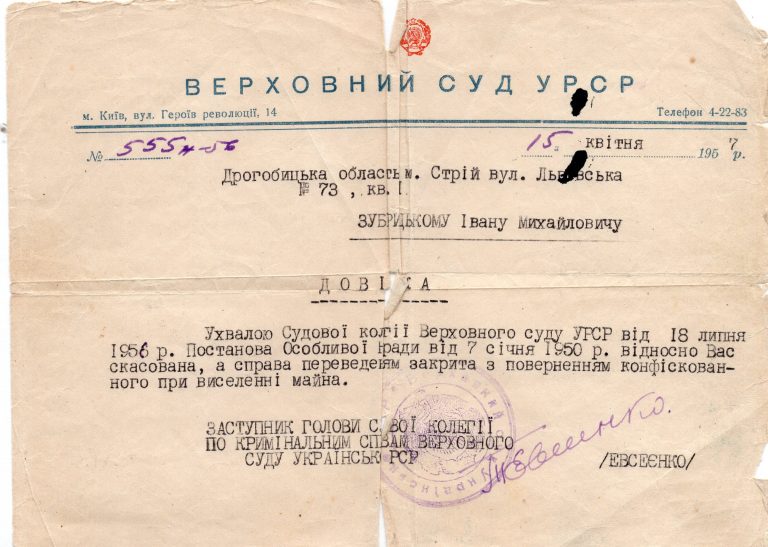

Director Sochniev from Khabarovsk noticed her father’s diligent work and soon suggested that Zubrytski move. Ivan continued to work as an accountant, however, now in the association of factories, and Mariya worked as a passport officer in the barracks services unit. In April, they were notified of a decision by the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR to overturn an eviction order and close the case. The family began to get ready for returning home to Stryi. Obtaining a certificate was a vital decision for Sofiya Zubrytska – “it was a very important document for us, it was practically our pass for all the… for life.”

The certificate also stated that “the case should be closed with the return of the property confiscated during the eviction”, but when Sofiya and her parents returned to Stryi, their former apartment was occupied – “of course, our apartment, and everything we had was immediately taken away, on the same day we were evicted, in the evening the chief of the regional department of militia moved into our apartment”. The family began living in a rented apartment, and after her brother and family friends returned from Siberia and helped him get a job in a mine in Novovolynsk, they moved there.

Sofiya Zubrytska entered and graduated from the Pedagogical Institute in Lutsk. After working for several years in Novovolynsk, in 1968 she moved to Lviv, where she began teaching mathematics, and three years later became a deputy principal, and three years later – a principal. And so having worked for 10 years at school on the Leontovycha street, in 2010 she retired.

“There have never been any drunks or absentees in our family because we have always been taught from an early age: we must be better because we have a stigma. And this stigma, of course, followed us all our lives. Brother, my brother was highly valued as an employee, but when his wife once asked the head of the department, she said: “Well, well, you appreciate him so much, you take his reports and present them. Why don’t you make him director of the mine?” He says, “Because you have an entry,” he says, “I wanted to, but when it comes to where we grew up, that’s it.” Doesn’t matter, however, we all graduated from higher education, we all received normal profession, right? And it seems to me that we have done a lot of good deeds in our lives.”

Rehabilitation decisions