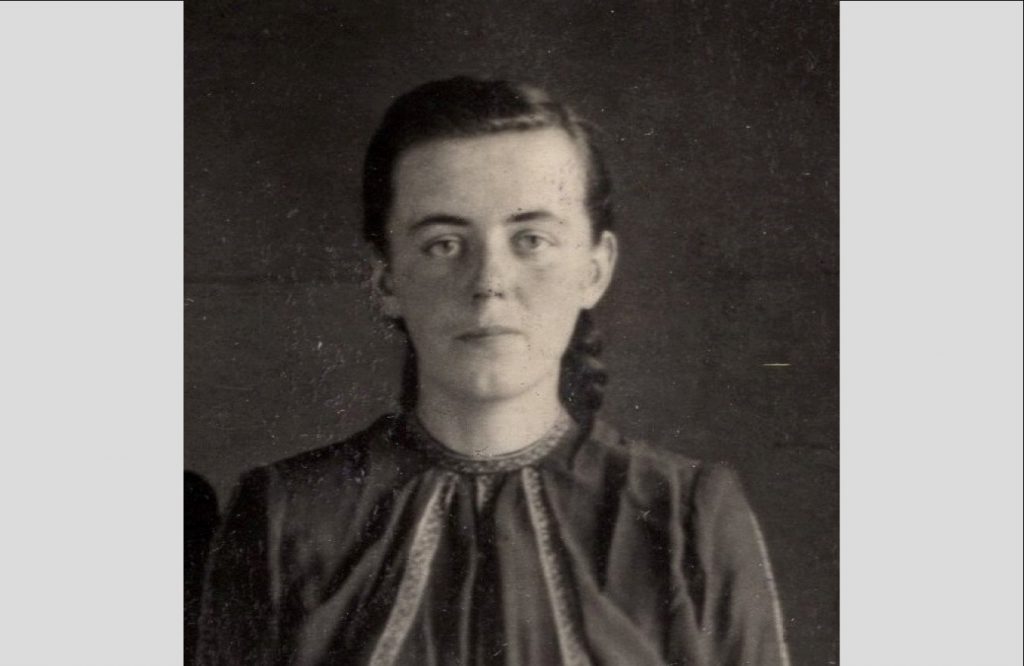

Zenoviya Strochan

Born on May 29, 1932 in Zozuli village, Zolochiv district, Lviv oblast. Had a sister and a half-brother Yaroslav.

I don’t want your gold, go.

As a little girl Zenoviya remembered the Nazis’ crimes – some things she heard herself and her parents told her some things too:

“It was, wait, in some year…they dug a pit on the outskirts of Zolochiv and the Germans were taking them there. They shot them: Bang-bang-bang, we could hear it, and they were falling, even alive; then they climbed out at night and wandered around the village and told everyone. A Jew from that lot even knocked on our door: “Ivan, Ivan, a place…to stay. Hide me, I’ll give you a lot of gold!” But my dad said: “No! I don’t want you gold. Go away. They will shoot me and destroy my family. I don’t want your gold, go”. So he went away, sick at heart. Goodness knows where he went and whether they caught him or not, for later they were going around the village and shooting. Those who caught Jews even shot those people who were hiding them. But those were rich people, they said their homes were in Zolochiv not far from Kamenets; they said the gold was hidden where their houses used to be. He said take it. But my dad didn’t want it. Still, there were people who turned rich, pulled through somehow, these things happened too”.

There were our boys, they were digging hideouts

When the Soviet regime returned, it started fighting the Ukrainian underground resistance movement.

They were asking Zenoviya too: “Our local policeman wasn’t good. He kept calling us children up and [asking] whether Bandera supporters visited us or not. We were told not to say a word – we don’t know, we know nothing”. NKVD soldiers brought bodies of killed resistance fighters to be recognized: “It was awful, they were catching them, took them to Zolochiv near the church and beat them, then sat them outside the church. One of those went up to the fourth floor and looked through the window to see whether relatives would come… Everyone was allowed to come and watch, and many people came. Even the relatives came to watch. No one could admit they were family, these were terrible times, you know”.

Her half-brother Yaroslav also joined the resistance movement. He was wounded during a raid. His further destiny is unknown. Rumour had it that a neighbour saw his dead body.

He would come and say: “Ivan, you will go to Siberia, you surely will”.

District police inspector Mytriokhin threatened Ivan Strochan with deportation because of his being an underground fighter:

“There was a Mytriokhin. He was a bad man. He kept coming and saying: “Ivan, you will go to Siberia, you surely will ”. The Strochans were deported in 1947. “We all went to bed. They encircled the house. Lots of soldiers. Going by carts and cars, they encircled the entire village; they were supposed to fight Germans or something… And that was it: Get up, pack your things, that’s it. But we just…one loaf of bread… Mom was planning to bake bread tomorrow. There was no food, just some cereal. Potatoes, all of that, was, well… And like I said: pack up, this district policeman didn’t let us take anything. He came up, there were pillows, he threw two pillows and a duvet, something like that. Some stuff to wear, only some rags, he threw some in, tied it up – harness a horse, Ivan. They put us on a cart. There used to be a school in Zozuli where a shop is now. There were lots of soldiers around that school, and all people were brought in there”.

“We were gradually turning wild”

People were instantly transported from the collection point in Zozuli to the railway station and put on an echelon:

“They put us on a wagon. A freight car. There were no berths, just two boards put on top of one another. There were benches on the upper deck, and many families lived there. There was no place to sleep. Our people were sitting on those boards, nodding. We were gradually turning wild, we didn’t wash or take care of ourselves. Whoever had something, they came to sell. Everyone was at the railway stations. They were handing out water. There was a stove with two buckets of coal around it. We were boiling the water and drinking tea. I don’t remember then how much time we rode. But it was very long, and we even stopped at railways for a long time. We were put on a dead end, where lots of people and wagons were. There were guards nearby and they watched us. When we needed to bring in some water or something, they would only let us take a couple of people, that was it. So you know (…) when people died, and they were still transported. Then they opened the wagon where the pit was, grabbed the dead one by the feet and threw them out, that’s the whole story. Where are those people, did someone bury them?”

Ivan’s brother-in-law saved the entire family from famine. He bought a sack of bread, bribed the guard and could give it into the wagon through the window.

“Goodness, I was crying, they would say that you, Banderite, contrived something”

he people were brought to Prokopievsk town, Kemerovo region (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic). First lice-ridden people were taken to baths, and their clothes and personal belongings were treated with heat. Then they settled us in barracks. Started employing at a coal mine. There were too many special setters, so some were taken to the north of the region, to Leninsk-Kuznetskiy. The Strochans family were among those. The people were settled in barracks and started working at Karl Marx coal mine. A 15-year-old Zenoviya worked at a mine as a horse handler. These were unknown and difficult labour conditions for a teenage girl:

“As soon as the coal mine opened, That plot was under water. I was a horse handler and two horses were killed. There was lots of water and some cable hanging low. It was a mess, and once I was driving using a pulling hoist, the entire train with wooden carriages. I stopped, and started shaking, and the horse turned and fell. Goodness, I was crying, they would say that you, Banderite, contrived something. But I did nothing, nothing at all. There was a committee and they called me in; but they did nothing, just asked me questions. It’s ok, there was another section. Well, we grew to love one another, it was hard work, we were using shovels and so on”.

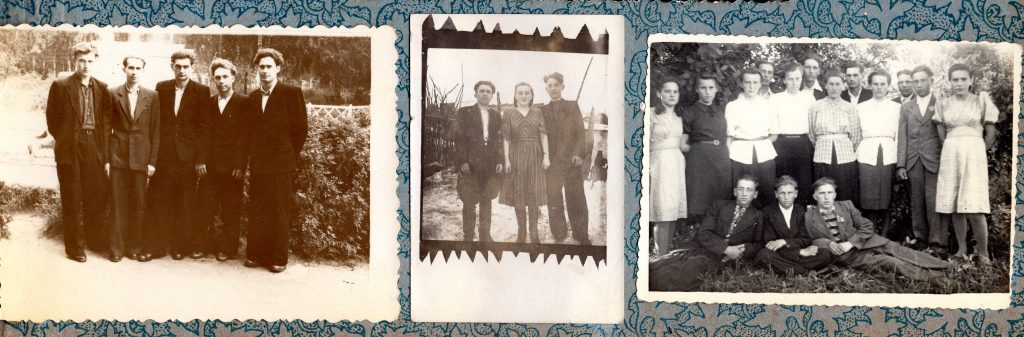

(photo: School in Siberia)

The father and Zenoviya supported the family. The child labour didn’t bring much money: “They were paying us, but very little, 20 or 25 roubles, it wasn’t enough”. The mother stayed home and took care of the family. The sister first went to school. There wasn’t enough money all the time, so her sister started helping her family she only way she could: “Then my sister went, someone prompted her… There wasn’t enough money for food”. We were walking around the field, picking up potatoes to have something to eat, that the way it was”.

Then the sister went to work at a factory “behind the high fence”, the name of which has never been mentioned. The first moths she earned more money than her family at a coal mine. It’s only later that the father learned there was a chemical plant behind that tall fence: “The father asked people what it was and what kind of money it was. They told him: “Ivan, do you know where your child is? It’s a chemical plant, she can’t stay there for a long time. People would start working there, they get their payment, but it harms her health. And you sent there some little child”. The girl left her job as the father insisted: “In some time she was home, then she found a place to serve as a nanny to a boy. She was also doing some other job somewhere”.

Soon the family’s financial situation improved. The Strochans bought a mad hut for two families. They were running a house.

Zenoviya married a deported Ukrainian Slavko who came from Pochapy village, Zolochiv district, Lviv oblast. They gave birth to two children.

After Stalin’s death the Strochans were released. All family members could return home. The parents were the first to come back to Ukraine. They took all the savings, as there was nothing to come back to. All their property was confiscated during the deportation. Zenoviya and her husband spent another five years in Siberia. Despite his poor health, Slavko went to work at the chemical factory to earn money. The couple send the money to Ukraine to their parents. They used it to build a house. Only after that Zenoviya’s family came back home.

There was not enough work in Zolochiv, so, following the advice of former political prisoners, the family moved to Chervonohrad where Slavko started working at a coal mine. That’s how he managed to get a flat for his family. On the contrary, Zenoviya’s parents stayed in the house they built.

The story of Mrs. Zenovia’s sister can be found at: