Yaroslav Hera

Born on 19 December 1932 in Liatsko village (presently Solonuvatka village, Sambir district, Lviv oblast). His parents, Stepan and Mariya, were farming their own land. Besides Yaroslav, they were bringing up their younger daughter Mariya born in 1937.

Yaroslav remembers the Communist terror during the first Soviet occupation:

“I saw them chasing those people off over there from Przemysl – take it, the 20 kilometres distance, and each of those people who thought that (…). They took all this cohort to Salina and threw into salt mines; a tractor was running to choke up all that noise and shouting”.

He remembers the second advent of the Soviet regime too: “Before that the things were like this: Soviet troops were advancing and the Germans retreated. The soldiers were stationed at the stadium, there were artillery guns and a Katiusha [Soviet multiple rocket launcher], so Bohdan and I decided to look around. I gave an apple to a soldier… “Do you have milk?” “Yes, we do have milk”. We had two cows. We didn’t know what kind of people they were, but we gave them some milk. We gained their trust so that we managed to steal a cartridge box and an ammo belt from them”.

(photo: Parents: Stepan, Maria. sister Maria, Yaroslav (the whole Hera family) 1940. Lyatsko village).

Later Bohdan pinched an assault rifle from a Red Army soldier and the village boys were learning to shoot firearms under the supervision of the UPA [the Ukrainian Insurgent Army] fighters. UPA guys regularly came to their hiding place and asked where the village boys got ammunition. The latter kept back the truth for quite some time, but eventually revealed the location of their cache. The next morning the ammo wasn’t there.

“They said in 1950: “Kolkhoz or Siberia”.

Yaroslav’s family had close ties to the underground resistance movement; several family members were UPA fighters and his parents served as freedom fighters’ liaison. They were under the NKVD [secret police] suspicion. The first search of the Heras’ household happened in 1947, but no proof of their links to the resistance movement was found. During the second search in early autumn the NKVD officers found an empty hiding place in a shed. Mariya Hera was detained and severely beaten during interrogations. However, they never received the information they wanted. They released Mariya after two months, but she suffered the effects of the tortures till her death in 1986.

(photo: Mykhailo Protsak in the UPA, 1940s. Aunt’s brother)

In 1950 Yaroslav’s parents were forced to join the kolkhoz: “My father told me they took everyone to the village council and stuck their fingers in the door to make them sign. Your right hand was stuck in the door so you had to use the left hand to sign”. It didn’t save them from further repressions.

Boryslav, transit point

The family (father, mother, Yaroslav and his younger sister Mariya) were deported in August of that year. First, they were kept at the Boryslav transit point.

Yaroslav remembers staying there: “Sometimes they fed us and sometimes didn’t, but we needed to eat, both children and adults. There was this common kitchen, a mess; everyone was queuing and cooking something. And what were we, the boys, doing? Messing around”. They were waiting at the transit point till a sufficient number of people arrived to be transported: “They would bring in new people, even those from our district that we knew more or less, as we went to Dobromyl school together”. After several months the deportees were put on an echelon. “Around late September – early October they split us into groups, by surnames, but tried to keep people from the same village apart”.

The road to deportation

The deportees instantly faced some daily challenges: “There was a toilet in the wagon by the wall. It was made of planks. Girls and women had to make an improvised partition to be able to use the toilet. The toilet was broken and they had to manage it the best way they could”.

The echelon stopped at large stations, the train was put on a dead-end track and heavily guarded. There were duty men from each wagon. “Only girls and older women were entitled to go out with buckets to bring some soup or whatever was handed out or bring some water”. Older boys and young men would put on lady’s dresses and kerchiefs and, posing as girls, would go to the food dispensary. However, the guards soon tracked them down: “We were caught. People not only from our wagon; but there was something that gave us out. It took some time and effort for a girl or a woman to climb on the wagon. But we came, threw the sacks up and got on the wagon in one move”. They were punished for it: “We were properly punished, those who were caught and not only them. People from our wagon and some other wagons did not receive any water or food during certain distances as a punishment”.

At the special settlement

The echelon arrived at Khabarovsk. After a day’s waiting the deportees started being transported to their destinations. The Heras first got into Zbruchiy village and then moved to Bachikha special settlement. All adult men had to work as lumberjacks: “Women weren’t working. But all of us did what we could. Some of us were cutting trees, some removed the branches and some burned them. That’s how we spent almost the entire year”. They were put up in two former barracks for Japanese POWs.

Yaroslav Hera together with a deportee Iosyp Hural decided to enter Khabarovsk maritime school in 1951. However, the director refused them because of their special settlers’ status: “I would be happy to admit you, but you’ll be taken away and punished. Even if you manage to graduate, no matter the grades, they won’t allow you to join the navy. We are training boys to become sailors or other personnel working at sea, and they won’t let you in”. However, the maritime school director made a call to the director of Khabarovsk trade school. Together with other boys deported from the Western Ukraine they started going to that trade school. The authorities started searching for Yaroslav at the special settlement, as he was absent for a long time: “They found us approximately in a year. Not the two of us only, half students in that school were from Western Ukraine. We were finishing the second year of studies and worked at a plant. Militia came to the director searching for us. There was the national level order issued in the USSR, so they didn’t take us from that school. Then we worked in Khabarovsk, at Gorkyi plant.

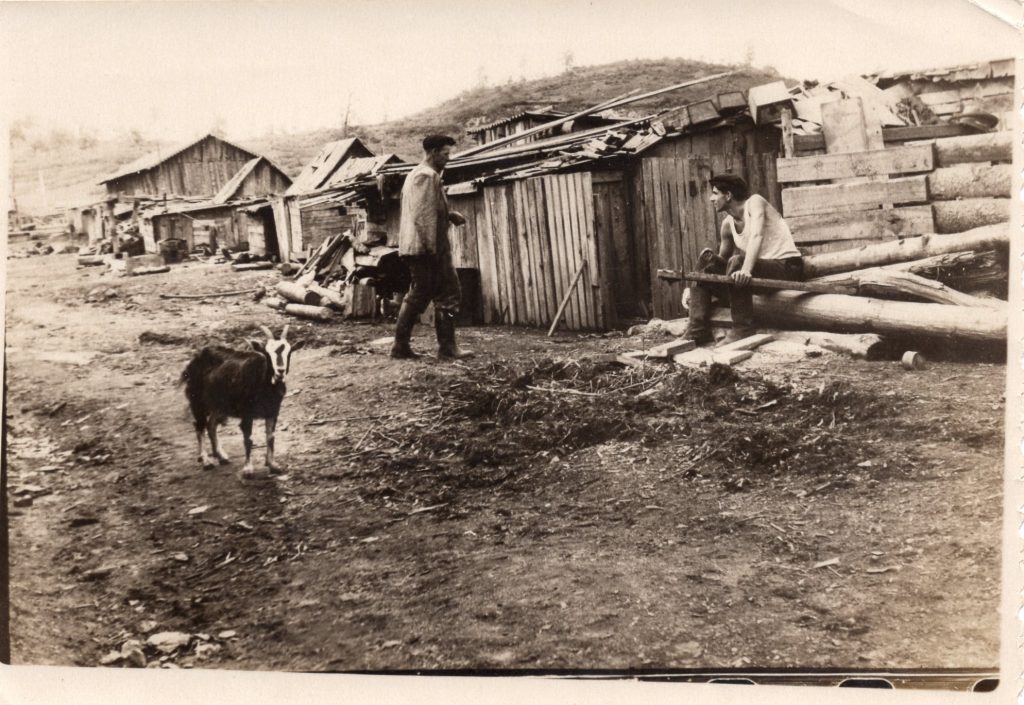

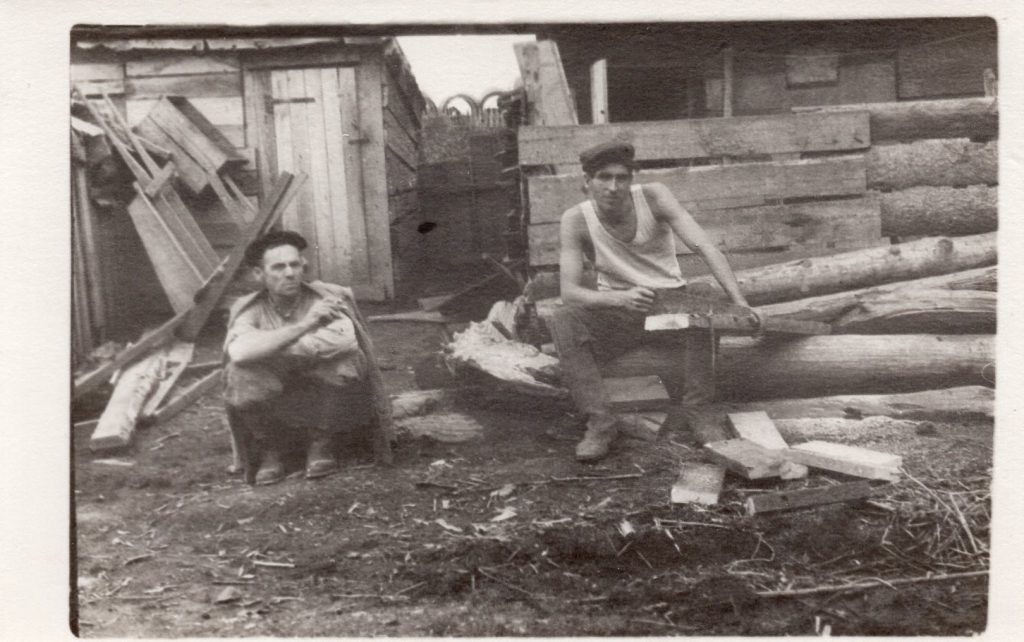

(photo: Father of Yaroslav Hera, with a friend, 1950).

Coming home

Meanwhile, Yaroslav’s parents and sister were relocated to a special settlement at Lytovka station where they used to keep prisoners.’ After Stalin died, deportees started being issued passports. In 1955 Yaroslav’s parents moved to Teple Ozero [Warm Lake] station where their home folks lived. They were getting ready to return home together. Eventually, all of them set off for the trip back home. Having finished his studies, Yaroslav was working in Khabarovsk Krai for some time. “I learned a trade at the technical school and worked at the power generating unit as an on-duty energy worker”. In a year’s time he also set off for home.

Still, there was no home to return to. The Soviet authorities took away all the property after the family’s deportation. Their house was given to deportees from Poland. The family stayed with mother’s sister until they moved to Lviv.

(photo: Yaroslav HERA after the exile)

In 1960 Yaroslav finally moved to Lviv, He graduated from technical school of communications there. Later he enrolled in the 3rd year of Lviv Polytechnic University where he got his university degree. His parents came to Lviv in 1963.